News

Churches Conservation Trust Debate

03.09.2019There are 16,000 parish churches in England, many of them representing a great legacy of England’s local culture. However, with congregations dwindling, who is going to look after them in the future?

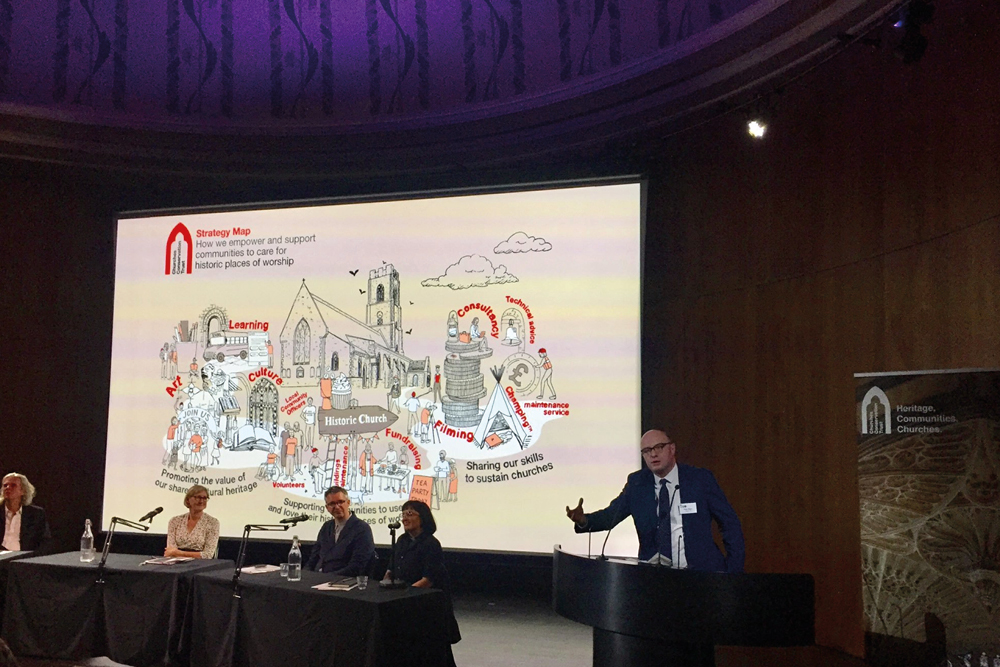

We were delighted to take our place on the panel for this discussion as part of the Churches Conservation Trust’s ’50th Anniversary Debate: Who should be responsible for the care of historic churches?’. Organised as part of the CCT’s Golden Anniversary celebrating 50 years of saving historic churches, Sir Simon Jenkins, writer and broadcaster and Trustee of the CCT, lead the debate at the V&A Museum in London, following an introduction from Director Dr Tristram Hunt.

Nick Berry from OMI joined the discussion alongside Peter Stanford, the award-winning writer, journalist and broadcaster and Revd. Sally Hitchiner, broadcaster and Associate Vicar at St.Martin-in-the-Fields.

Nick’s opening statement can be read in full below:

“I will start off, by way of a disclaimer, to say that I’m not a Conservation Architect and as a practice we don’t do any work as retained church Architects dealing with day to day historic repair issues.

My own experience is therefore flavoured by the church work that we do undertake which is by and large in the fields of re-use and re-development.

We have 2 main client groups.

Firstly we work for active churches, who are generally looking to expand their activities to provide facilities for different church and community groups on a 7 days a week basis. These projects can range from simple re-ordering to create more flexible space within the church, to large scale alterations and extensions to the existing church to provide different types of space for different users.

In relation to the question – “who should be responsible for the care of historic churches” it could be argued that for these active churches it is not really a question. Many of these groups have large congregations of often committed young professionals who make regular and not insubstantial donations to the church coffers. The repair and upkeep costs are generally met through good stewardship and in our experience even the costs for undertaking significant extensions can be substantially raised, within the congregation. This is often through sacrificial giving where the they see the potential of the building to support the church’s missional aims within the local community.

Some might say that this is not dissimilar to the way that churches were funded in the days when they were built with taxation from the congregation (which was more or less everyone) paying the bills. You might also be tempted to think that this serves as a model for the problem of funding churches generally, but it must be remembered that this is a particular niche and interesting as it is, it probably only accounts for a very small minority of the 16,000 churches across the country.

By contrast, the other type of client is the owner or custodian of a redundant church looking at ways to bring it back into use and make it self-sustaining – often after a long period of neglect that has resulted in a massive cost deficit in terms of its repair bill.

The CCT is one of these clients and deals with this issue on a daily basis.

Some of you may be aware of the project at All Souls’ Bolton that we worked on with the Trust. All Souls was a large redundant parish church which had once served a community of mill workers in Bolton, designed for a congregation of 800. After a long period of decline of both industry and congregation, it was eventually closed in 1986.

After 25 years of essential only ‘sticking plaster’ maintenance and sustained attacks of vandalism and anti-social behaviour, a project spearheaded by a local community group and supported by the CCT was born that would see All Souls’ brought back into use as a local community building.

The project took 10 years to complete and the costs where huge. The repair bill alone was in excess of £1M and the conversion required to make the building suitable for the range of uses that it now supports was more than double that. This level of expenditure could never have been met by the community at All Souls and in its day to day operation relies on constant management to ensure that it can remain self-sustaining.

These projects are not easy and if it was not for the substantial grants provided by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Historic England and others, which totaled about £4.5M, this project could not have happened.

The particular approach at All Souls is not suitable for all churches and not all churches need expenditure at that level, but the great success of All Souls’ is that it shows that there is a role for churches as community buildings – perhaps returning to them to their origins, when churches would have been used for a whole range of functions outside of their primary purpose.

Churches are the most significant heritage building in most towns and villages across the country and would fit into most people’s view of an ideal English village (albeit in close competition with pubs – which is a whole different conversation…… watch this space for our first pub/ church combination project!). Churches are part of our collective cultural identity and no-one wants to see them disappear.

I accompanied CCT Chief Exec Peter Aiers on a very small leg of his epic 50 churches in 50 hours event in July and was amazed at number of people who were prepared to turn out in the middle of the night in many cases by torch light, to act as a welcome party – people do care about their churches and want them to see them survive.

There is also a desperate need for community facilities in most areas and re-purposing churches would seem an ideal way of providing these facilities whilst bringing new life to these important heritage buildings.

We, as a profession, have a sophisticated enough understanding of significance to be able to undertake quite radical conversions without destroying the defining attributes of an historic building – we have the skills, we have the need and we have the community will – what’s missing is the funding required.

In my view there has to be a way in which state funding can be re-directed towards the upkeep and re-purposing of what are some of our most valuable heritage assets to create buildings which can once again play an important role in our communities.”